[The Fall 2020 edition of The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories will be "Some More Untold Cases" - Thus, this essay is being presented on my irregular blog, a version of which originally appeared as my Editor's Foreword of The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories: Some Untold Cases - Part XI (1880-1891) and Part XII (1894-1902)]

There are certain numbers that are triggers to deeply passionate Sherlockians. One of these is 221. I’ve discussed this with other people of like mind. If you’re one of us, you know that feeling – when you’re going through your day and look up to see that it’s 2:21 – hopefully in the afternoon, because you should be asleep for the other one. Seeing that it’s 2:21 o’clock is always a little thrill.

One can encounter 221's all over the place. Who doesn’t get a pleasant surprise when seeing that there are 221 miles left before the car runs out of gas?

Or what about when gas is $2.21 per gallon? (Make no mistake - that's still too much, but it's an aesthetically pleasing price if you're a Sherlockian):

Sometimes a lucky Sherlockian will be assigned 221 as a hotel room.

In her retirement home, my mother-in-law lived next door to someone in Room 221, and I couldn’t walk by that door without noticing it every time. Maybe you have an office numbered 221 - or at least you might have an appointment in one. If you’re very lucky, your house number is 221 – and I wonder how many non-London Baker Streets are there scattered throughout the world that have a 221 address?

Here’s a house not far from where I live with the almost-correct number of 2213. I’d be so tempted to add a line down the left side of that 3 . . . .

I often notice when I reach page 221 in a book, and I know from asking that other Sherlockians do the same. I was tickled a couple of years ago, while re-reading the stories in Lyndsay Faye’s excellent collection of Holmes adventures, The Whole Art of Detection, to see that the story she’d written for the first MX collection, “The Adventure of the Willow Basket”, began on page 221.

Even better is Profile by Gaslight (1944), in which Edgar W. Smith made Page 221 into Page 221b:

Any American interstate that’s long enough will have a marker for Mile 221, and just east of Nashville, Tennessee, about three hours due west of where I live, and where I’m sometimes able to attend meetings of The Nashville Scholars of the Three Pipe Problem – a scion of which I’m a proudly invested member – there’s a big sign for Exit 221B on the eastern side of Interstate-40. My deerstalker and I have several photos in front of it.

Best of all is when you can visit the most famous 221 in the world - in Baker Street, London:

221 is a number that makes a Sherlockian look twice, but there’s another – 1895.

Always 1895 - or a Few Decades on Either Side of It . . . .

1895 is a year that falls squarely within the time that Holmes was in practice in Baker Street – and I specify that location, because he had a Montague Street practice and unofficially a retirement-era Sussex practice as well, where he carried out the occasional investigation, while also spending a great amount of time first trying to prevent, and then trying to prepare for, the Great War of 1914-1918. But he was in Baker Street from 1881 to 1891 (when he was presumed to have died at the Reichenbach Falls,) and then again from 1894 (when he returned to London in April of that year) until autumn 1903, when his so-called “retirement” began, before he began his efforts leading to prevenging, or at least delaying, the great global war that was looming in the distant future.

1895 isn’t especially known as Holmes’s busiest or most famous year. Make no mistake, there were some interesting cases then: “Wisteria Lodge”, “The Three Students”, “The Solitary Cyclist”, “Black Peter”, and “The Bruce-Partington Plans”. But 1894 is when Watson specifically mentions, in “The Golden Pince-Nez”, the three massive manuscript volumes which contain his and Holmes’s work. And it was the 1880’s, before The Great Hiatus, where all of those beloved adventures recorded in The Adventures and The Memoirs occurred. “The Speckled Band”, possibly one of the most famous of them all, took place in 1883. All four of the long published adventures, A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of the Four, The Valley of Fear, and perhaps the most famous of tales, The Hound of the Baskervilles, occur chronologically before 1895.

And yet, 1895 is still the representative year most mentioned by Sherlockians – “where it is always 1895” said Vincent Starrett at the conclusion of his famous poem 221B, written in 1942, and so it is subsequently referenced in essays and gatherings and toasts as the year.

Written in the early days of U.S. involvement in World War II – but several years after much of the rest of the world had already tipped into the conflagration – the closing couplet of Starrett’s poem reflects his likely despair at the terrible conflict:

Here, though the world explode, these two survive,

And it is always eighteen ninety-five.

I’m not a Starrett scholar, but I suspect that he was looking back to a more innocent time – or so it seemed when compared to the terrible war-torn world of 1942. (For many of the people actually in 1895, the world was a relatively terrible place for them too, for all kinds of different reasons.) But did Starrett simply mean to invoke the whole Holmesian era, a bygone past, or did he specifically want to focus on 1895? It’s likely that the former is true, and that he simply used 1895 because five rhymes with survive. It could have just as easily have been a different number – although with less effect:

Here, though the world explode, these two are fine,

And it is always eighteen ninety-nine.

Imagine – but for a different word choice, we could have been finding ourselves misty-eyed when referring to 1899. Or Starrett could have used 1885 and made the original rhyme work. Still, it’s 1895 that we have, and so that’s what we’ll be going on with as the year that we associate with Mr. Holmes and Dr. Watson – although I’m quick to point out that it’s 1895, along with several decades on either side of it!

Sixty Stories

Having explored 221 and 1895, there’s another Sherlockian number that might not immediately spring to mind, but that doesn’t diminish it, because it holds a great deal of power for some Sherlockians. That number is 60 – as in, Sixty Stories in the original Sherlockian Canon. For some die-hard types out there, this is it. No more, forever, period, finis, The End. There can only be sixty Holmes stories, and anything beyond that is fraudulent abomination. (Except, of course, for those one or two stories on their lists that get a rule-bending free pass.) It’s amusing for me to read various scholarly works, such as Martin Dakin’s A Sherlock Holmes Commentary (1972), that don’t even really like all of the original sixty Canonical adventures, let alone anything post-Canonical, picking apart the originals and speculating that this or that later Canonical narrative is a forgery.

I don’t buy into that philosophy. Early on, I ran out of Canonical stories to read and I wanted more. And I found them – some admittedly of lesser quality, but some better than the originals. (It's true.) Even at a young age, I understood that some of the original tales weren’t quite as good as others, but those first sixty stories, presented by the First Literary Agent and of whatever varying levels of quality, were about the true Sherlock Holmes, and they let me visit in his world, and I wanted more. Thankfully, before I’d even read all of The Canon, I’d discovered those post-Canonical adventures designated as pastiches, so even as I re-read the original adventures countless times, I also read and re-read all of those others that told of new cases, or filled in the spaces between the originals.

Luckily, even Watson never acted as if Holmes only solved sixty cases and that was it. No matter how intriguing a personality is Sherlock Holmes, or how vivid his adventures are that they make a visit to Baker Street sometimes more real than tedious daily life, how could we truly argue that he’s the world’s greatest detective based on a mere and pitifully few sixty stories?

In “The Problem of Thor Bridge”, Watson tells us that:

Somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox and Co., at Charing Cross, there is a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch box with my name, John H. Watson, M.D., Late Indian Army, painted upon the lid. It is crammed with papers, nearly all of which are records of cases to illustrate the curious problems which Mr. Sherlock Holmes had at various times to examine. Some, and not the least interesting, were complete failures, and as such will hardly bear narrating, since no final explanation is forthcoming. A problem without a solution may interest the student, but can hardly fail to annoy the casual reader . . . Apart from these unfathomed cases, there are some which involve the secrets of private families to an extent which would mean consternation in many exalted quarters if it were thought possible that they might find their way into print. I need not say that such a breach of confidence is unthinkable, and that these records will be separated and destroyed now that my friend has time to turn his energies to the matter. There remain a considerable residue of cases of greater or less interest which I might have edited before had I not feared to give the public a surfeit which might react upon the reputation of the man whom above all others I revere. In some I was myself concerned and can speak as an eye-witness, while in others I was either not present or played so small a part that they could only be told as by a third person.

Thank goodness this incredible Tin Dispatch Box has been accessed throughout the years by so many later Literary Agents to bring us all these other wonderful Holmes adventures. Many that have been revealed have been complete surprises, but sometimes we’ve discovered details about a special group of extra-Canonical adventures, those that fire the imagination to an even greater level: The Untold Cases.

(I've had my hands on that Tin Dispatch Box several times, such as this occasion ....)

The Untold Cases

Of course, they aren’t called "The Untold Cases" in The Canon. The earliest references to The Untold Cases that I’ve heard of so far (with thanks to Beth Gallegos) are by Anthony Boucher in 1955, and by William S. Baring-Gould in his amazing The Chronological Sherlock Holmes (1955). Additionally, Charles Campbell located a reference to “stories yet untold” by Vincent Starrett in “In Praise of Sherlock Holmes” (in Reedy’s Mirror, February 22, 1918). The Untold Cases are those intriguing references to Holmes’s other cases that – for various reasons – were not chosen for publication. There were a lot of them – by some counts over one-hundred-and-forty – and in the years since Watson’s passing in 1929, many of these narratives have been discovered and published.

For example, The Giant Rat of Sumatra . . . .

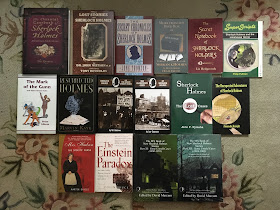

Since the mid-1990’s, I’ve been chronologicizing both Canon and Pastiche, a massive project that is now around 1,000 dense pages of material, and as part of that, I note in my annotations when a particular narrative is an Untold Case. Glancing through my notes, I see that there are far too many narratives of The Untold Cases to list here. Just a quick glance through my own collection and Chronology reveals, in no particular order, multiple versions of perhaps the greatest and most intriguing Untold Case of them all, The Giant Rat of Sumatra:

• The Giant Rat of Sumatra – Rick Boyer (1976) (Possibly the greatest pastiche of all time, shown here in several editions in my collection)

Then there are several novel-length versions that mention the Giant Rat in the title:

• The Giant Rat of Sumatra – Jake and Luke Thoene (1995)

• The Shadow of the Rat – David Stuart Davies (1999)

• The Giant Rat of Sumatra – Daniel Gracely (2001)

• Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra – Alan Vanneman (2002)

• Sherlock Holmes’ Lost Adventure: The True Story of the Giant Rats of Sumatra – Laurel Steinhauer (2004)

• The Giant Rat of Sumatra – Paul D. Gilbert (2010)

Quite a few others refer to the Rat during the course of the narrative . . . .

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The Oriental Casebook of Sherlock Holmes – Ted Riccardi (2003)

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The Lost Stories of Sherlock Holmes – Tony Reynolds (2010)

• “The Case of the Sumatran Rat”, The Secret Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes – June Thomson (1992)

• “Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, More From the Deed Box of John H. Watson MD – Hugh Ashton (2012)

• “The Case of the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The Secret Notebooks of Sherlock Holmes – Liz Hedgecock (2016)

• Sherlock Holmes and the Limehouse Horror – Phillip Pullman (1992, 2001)

• “The Mysterious Case of the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The Mark of the Gunn – Brian Gibson (2000)

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, Resurrected Holmes – Paula Volsky (1996)

• “All This and the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, Sherlock Holmes and The Baker Street Dozen – Val Andrews (1997)

• “Matilda Briggs and the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The Elementary Cases of Sherlock Holmes – Ian Charnock (1999)

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, Sherlock Holmes: The Lost Cases – Alvin F. Rymsha (2006)

• “No Rats Need Apply”, The Unexpected Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Amanda Knight (2004)

• Mrs Hudson and the Spirit’s Curse – Martin Davies (2004)

• “The Case of the Missing Energy”, The Einstein Paradox – Colin Bruce (1994)

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Part XII: Some Untold Cases (1894-1902) - Nick Cardillo (2018)

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Part XI: Some Untold Cases (1880-1891) - Leslie Charteris and Denis Green (1944, 2018)

And since I gathered all those for a photo and originally posted this blog entry, I've come across another version, this one by Bob Bishop:

Additionally, there are a few other appearances out there, including, but not limited to . . .

• “The Giant Rat of Sumatra” – Paul Boler (Fan Fiction - 2000)

• “The World is Now Prepared” – “slogging ruffian” (Fan Fiction - Date unverified)

• “The Adventure of the Giant Rat of Sumatra”, Mary Higgins Clark Mystery Magazine – John Lescroart, (December 1988)

In addition to the versions of The Giant Rat that are available, there’s also one that isn’t – possibly the earliest telling of it in the intriguing lost radio script by Edith Meiser, broadcast on multiple occasions: With Richard Gordon as Holmes on April 20th (although some sources say June 9th), 1932, and again on July 18th, 1936; and then on March 1st, 1942 (with Basil Rathbone as Holmes). Sadly, these versions are apparently lost, although I’d dearly love to hear – and read – them!

Although Rathbone and Bruce performed Edith Meiser’s version of “The Giant Rat” in 1942, they weren’t limited to just that version. A completely different version, this time by Bruce Taylor (Leslie Charteris) and Denis Green, was broadcast on July 31st, 1944. Amazingly, Charteris’s scripts have been located by Ian Dickerson, who is in the process of publishing them for modern audiences who would otherwise have never had the chance to enjoy these lost cases.

And even more amazing, Mr. Dickerson allowed the 1944 version of “The Giant Rat” to initially be published in The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Part XI: Some Untold Cases (1880-1891), as mentioned above.

Interestingly, Untold Cases have been presented in Holmes radio shows since the 1930’s, but they are much more rare in television episodes and movies. Sadly, except for some Russian efforts and a few stand-alone films, there have been absolutely no Sherlock Holmes television series whatsoever on British or American television since the Jeremy Brett films from Granada ended in 1994. Hopefully, a set of film scripts by Bert Coules featuring an age-appropriate Holmes and Watson, set in the early 1880’s, will find a home soon. I’ve been wanting to see (or read) these for years, and I’m curious as to whether any other Untold Cases feature in them – especially since Bert covered some of them so well in his radio series The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes:

It isn't only Holmes who has faced The Giant Rat. For instance, Inspector Lestrade, as portrayed in the nineteen (so far) novels by M.J. Trow, has crossed its path in Lestrade and the Giant Rat of Sumatra (2014). Some of the Lestrade novels by Trow can almost fit within a traditional Canonical framework. Some, sadly, cannot.

Every once in awhile the Giant Rat appears in something that isn't traditional or Canonical at all, such as when my very old (but always young) friends The Hardy Boys encountered it while carrying out an investigation involving a Sherlock Holmes Musical in No. 143 The Giant Rat of Sumatra (1997). I've been reading and collecting The Hardy Boys since I was eight years old in 1978, and I have all of them, every book, every series. I was thrilled when this volume appeared:

And then there are the world-threatening giant rats that my all-time favorite superhero, Captain Marvel - and he's Captain Marvel, and NOT Shazam! - faced in a story first published in 1953, and reprinted in my childhood in this 1975 comic, still in my Captain Marvel collection:

More than one version . . . .

The examples of Giant Rat encounters shown above is by no means a complete representation of all the Giant Rat narratives. These are simply the ones that I found when making a pass along the shelves of my Holmes Collection, and what jumped out during a quick search through my Chronology. The thing to remember is that in spite of every one of these stories being about a Giant Rat, none of them contradict one another or cancel each other out to become the only true Giant Rat adventure.

Something that I learned very early, far before I created my Chronology back in the mid-1990’s, is that there are lots of sequels to the original Canonical tales, and there are also lots of different versions of the Untold Tales. Some readers, of course, don’t like and will never accept any of them, since they didn’t cross the First Literary Agent’s desk. Others, however, only wish to seek out the sole and single account that satisfies them the most, therefore dismissing the others as “fiction” – a word that I find quite distasteful when directed toward Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

My approach is that if the different versions of either sequels or Untold Cases are Canonical, and don't violate the obvious rules: They aren't parodies, they don't contain anachronisms, there are no actual supernatural encounters, and Holmes isn't portrayed sociopathic murderer – then they are legitimate.

Perhaps it seems too unlikely for some that there were so many Giant Rats in London during Holmes’s active years. Not true. Each Giant Rat adventure mentioned above is very different, and in any case, Watson was a master at obfuscation. He changed names and dates to satisfy all sorts of needs. For instance, he often made it appear at times as if Holmes went for weeks in fits of settee-bound depression between cases, when in fact he was involved constantly in thousands upon thousands of cases, each intertwined like incredibly complex threads in The Great Holmes Tapestry.

There have been many stories about Holmes and Watson’s encounter with Huret, the Boulevard Assassin, in 1894. Contradictory? Not at all. Holmes simply rooted out an entire nest of Al Qaeda-like assassins during that deadly summer. There are a lot of tales out there relating the peculiar persecution of John Vincent Harden in 1895. No problem – there were simply a lot of tobacco millionaires in London during that time, all peculiarly persecuted – but in very different ways – and Watson lumped them in his notes under the catch-all name of John Vincent Harden. Later Literary Agents, not quite knowing how to conquer Watson’s personal codes and reverse-engineer who the real client was in these cases, simply left the name as written.

What Counts as an Untold Case?

As mentioned, there have been over one-hundred identified Untold Cases, although some arguments are made one way or another as to whether some should be included. Do Holmes’s various stops during The Great Hiatus – such as Persia and Mecca and Khartoum – each count as an Untold Case? (To me they do.) What about certain entries in Holmes’s good old index, like “Viggo, the Hammersmith Wonder” or “Vittoria, the Circus Belle”? Possibly they were just clippings about odd people from the newspaper, but I – and many other later Literary Agents – prefer to think of these as Holmes’s past investigations.

Then there are the cases that involve someone else’s triumph – or do they? – like Lestrade’s “Molesley Mystery” (mentioned in “The Empty House”, where the most well-known Scotland Yard inspector competently handled an investigation during Holmes’s Hiatus absence), or “The Long Island Cave Mystery”, as solved by Leverton of the Pinkertons, and referenced in “The Red Circle”. (And as an aside, I have to castigate Owen Dudley Edwards, the editor of the Oxford annotated edition of The Canon [1993], who decided to change the Long Island Cave to Cove simply because “there are no caves in Long Island, N.Y.” (p. 206) – thus derailing a long-standing point of Canonical speculation. Pfui!)

The Oxford Comma

And then there’s the matter of the Oxford Comma, sometimes known as the “Serial” or “Terminal” Comma. A quick search of the internet found this example of incorrect usage:

This book is dedicated to my parents, Ayn Rand and God.

Clearly this author either had some interesting parents, or more likely he or she needed to use a comma after Rand to differentiate that series of parents, Ayn, and Deity.

And that relates to Untold Cases in this way: There are two Untold Cases that might actually be four, depending on one’s use (or not) of the Oxford Comma. In “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez”, Watson tells of some of the cases that occurred in 1894. As he states:

As I turn over the pages I see my notes upon the repulsive story of the red leech and the terrible death of Crosby the banker. Here also I find an account of the Addleton tragedy and the singular contents of the ancient British barrow.

I have many adventures in my collection that present these as two cases: (1) The repulsive story of the red leech and the terrible death of Crosby the banker and (2) The Addleton tragedy and the singular contents of the ancient British barrow. All are very satisfying. But I also have others that split them up into four cases: (1) The repulsive story of the red leech and (2) the terrible death of Crosby the banker and (3) the Addleton tragedy and (4) the singular contents of the ancient British barrow.

As an amateur editor, I honor the Oxford Comma. I’ve been aware of it for years, ever since reading – somewhere – that editor extraordinaire Frederic Dannay (of Ellery Queen-fame and founder and the founding editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine from 1941-1982,) was a strong supporter of it. When writing this, I couldn’t remember where I’d read that, so I asked his son, Richard Dannay, who replied:

I can say with certainty that my father believed in the serial, or Oxford, or terminal (pick your poison) comma. I have no doubt. But sitting here, I’m not sure where he said that in print. I’ll need to think about that. But I will send you a secondary source, absolutely unimpeachable in accuracy, where his preference is described.

And then he sent me a PDF excerpt from Eleanor Sullivan’s Whodunit: A Biblio-Bio-Anecdotal Memoir of Frederic Dannay (Targ Editions, NY, 1984, pp. 17-18). Ms. Sullivan was Dannay’s chief editorial assistant for EQMM for many years, and after he died, she became the EQMM editor as his successor for about ten years before her premature death. (As Richard pointed out, the current editor is Janet Hutchings, only the third EQMM editor in its now over seventy-five-year history.)

Ms. Sullivan wrote:

Fred’s style in editing EQMM could be considered eccentric, but I soon became used to it because there was his special logic behind everything he did. I didn’t know he was exasperated by my non-use of the terminal comma (that is, a comma between the second-to-last word in a series of words and the “and”) until one day when we were discussing some copy I’d sent him, he sighed dramatically and said, “I wish you could learn to use the terminal comma.” I’ve been scrupulous about using it ever since.

Recalling Frederic Dannay’s passion for the Oxford Comma, I try to notice and then to add one in every place that needs it as I edit. Having hubristically stated that, I’m absolutely certain that there are places where I’ve missed them.

Other Untold Cases

As mentioned, there are far too many Untold Cases to list or recommend. The first encounter that I recall with attempts to reveal the Untold Cases was in The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes (1954) by a son of the First Literary Agent, Adrian Conan Doyle, and famed locked-room author John Dickson Carr. At the end of each of those twelve stories, a quote from The Canon revealed which Untold Case that it was – since it wasn’t always clear from the story’s title – and how it was originally mentioned.

2018's two-volume set The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories: Some Untold Cases - Part XI (1880-1891) and Part XII (1894-1902) contained 34 Untold Cases, and another similar set is planned for Fall 2020:

The Untold Cases - A List

The following list of Untold Cases has been assembled from several sources, including lists compiled by Sherlockians Randall Stock and the late Phil Jones, as well as some internet resources and my own research. I cannot promise that it’s complete – some Untold Cases may be missing – after all, there’s a great deal of Sherlockian Scholarship that involves interpretation and rationalizing – and there are some listed here that certain readers may believe shouldn’t be listed at all.

As a fanatical supporter and collector of traditional Canonical pastiches since I was a ten-year-old boy in 1975, reading Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution and The West End Horror before I’d even read all of The Canon, I can attest that serious and legitimate versions of all of these Untold Cases exist out there – some of them occurring with much greater frequency than others – and I hope to collect, read, and chronologicize them all.

There’s so much more to The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes than the pitifully few sixty stories that were fixed up by the First Literary Agent. I highly recommend that you find and read all of the rest of them as well, including those relating these Untold Cases. You won’t regret it.

A Study in Scarlet

• Mr. Lestrade . . . got himself in a fog recently over a forgery case

• A young girl called, fashionably dressed

• A gray-headed, seedy visitor, looking like a Jew pedlar who appeared to be very much excited

• A slipshod elderly woman

• An old, white-haired gentleman had an interview

• A railway porter in his velveteen uniform

The Sign of the Four

• The consultation last week by Francois le Villard

• The most winning woman Holmes ever knew was hanged for poisoning three little children for their insurance money

• The most repellent man of Holmes’s acquaintance was a philanthropist who has spent nearly a quarter of a million upon the London poor

• Holmes once enabled Mrs. Cecil Forrester to unravel a little domestic complication. She was much impressed by his kindness and skill

• Holmes lectured the police on causes and inferences and effects in the Bishopgate jewel case

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

“A Scandal in Bohemia”

• The summons to Odessa in the case of the Trepoff murder

• The singular tragedy of the Atkinson brothers at Trincomalee

• The mission which Holmes had accomplished so delicately and successfully for the reigning family of Holland. (He also received a remarkably brilliant ring)

• The Darlington substitution scandal, and . . .

• The Arnsworth castle business. (When a woman thinks that her house is on fire, her instinct is at once to rush to the thing which she values most. It is a perfectly overpowering impulse, and Holmes has more than once taken advantage of it

“The Red-Headed League”

• The previous skirmishes with John Clay

“A Case of Identity”

• The Dundas separation case, where Holmes was engaged in clearing up some small points in connection with it. The husband was a teetotaler, there was no other woman, and the conduct complained of was that he had drifted into the habit of winding up every meal by taking out his false teeth and hurling them at his wife, which is not an action likely to occur to the imagination of the average story-teller.

• The rather intricate matter from Marseilles

• Mrs. Etherege, whose husband Holmes found so easy when the police and everyone had given him up for dead

“The Boscombe Valley Mystery”

NONE LISTED

“The Five Orange Pips”

• The adventure of the Paradol Chamber

• The Amateur Mendicant Society, who held a luxurious club in the lower vault of a furniture warehouse

• The facts connected with the disappearance of the British barque Sophy Anderson

• The singular adventures of the Grice-Patersons in the island of Uffa

• The Camberwell poisoning case, in which, as may be remembered, Holmes was able, by winding up the dead man’s watch, to prove that it had been wound up two hours before, and that therefore the deceased had gone to bed within that time – a deduction which was of the greatest importance in clearing up the case

• Holmes saved Major Prendergast in the Tankerville Club scandal. He was wrongfully accused of cheating at cards

• Holmes has been beaten four times – three times by men and once by a woman

“The Man with the Twisted Lip”

• The rascally Lascar who runs The Bar of Gold in Upper Swandam Lane has sworn to have vengeance upon Holmes

“The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Speckled Band”

• Mrs. Farintosh and an opal tiara. (It was before Watson’s time)

“The Adventure of the Engineer's Thumb”

• Colonel Warburton's madness

“The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor”

• The letter from a fishmonger

• The letter a tide-waiter

• The service for Lord Backwater

• The little problem of the Grosvenor Square furniture van

• The service for the King of Scandinavia

“The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Copper Beeches”

NONE LISTED

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

“Silver Blaze”

NONE LISTED

“The Cardboard Box”

• Aldridge, who helped in the bogus laundry affair

“The Yellow Face”

• The (First) Adventure of the Second Stain was a failure which present[s] the strongest features of interest

‘The Stockbroker’s Clerk”

NONE LISTED

“The “Gloria Scott”

NONE LISTED

“The Musgrave Ritual”

• The Tarleton murders

• The case of Vamberry, the wine merchant

• The adventure of the old Russian woman

• The singular affair of the aluminium crutch

• A full account of Ricoletti of the club foot and his abominable wife

• The two cases before the Musgrave Ritual from Holmes’s fellow students

“The Reigate Squires”

• The whole question of the Netherland-Sumatra Company and of the colossal schemes of Baron Maupertuis

The Crooked Man”

NONE LISTED

The Resident Patient”

• [Catalepsy] is a very easy complaint to imitate. Holmes has done it himself.

“The Greek Interpreter”

• Mycroft expected to see Holmes round last week to consult him over that Manor House case. It was Adams, of course

• Some of Holmes’s most interesting cases have come to him through Mycroft

“The Naval Treaty”

• The (Second) adventure of the Second Stain, which dealt with interest of such importance and implicated so many of the first families in the kingdom that for many years it would be impossible to make it public. No case, however, in which Holmes was engaged had ever illustrated the value of his analytical methods so clearly or had impressed those who were associated with him so deeply. Watson still retained an almost verbatim report of the interview in which Holmes demonstrated the true facts of the case to Monsieur Dubugue of the Paris police, and Fritz von Waldbaum, the well-known specialist of Dantzig, both of whom had wasted their energies upon what proved to be side-issues. The new century will have come, however, before the story could be safely told.

• The Adventure of the Tired Captain

• A very commonplace little murder. If it [this paper] turns red, it means a man's life . . . .

“The Final Problem”

• The engagement for the French Government upon a matter of supreme importance

• The assistance to the Royal Family of Scandinavia

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

“The Adventure of the Empty House”

• Holmes traveled for two years in Tibet (as) a Norwegian named Sigerson, amusing himself by visiting Lhassa [sic] and spending some days with the head Llama [sic]

• Holmes traveled in Persia

• . . . looked in at Mecca . . .

• . . . and paid a short but interesting visit to the Khalifa at Khartoum

• Returning to France, Holmes spent some months in a research into the coal-tar derivatives, which he conducted in a laboratory at Montpelier [sic], in the South of France

• Mathews, who knocked out Holmes’s left canine in the waiting room at Charing Cross

• The death of Mrs. Stewart, of Lauder, in 1887

• Morgan the poisoner

• Merridew of abominable memory

• The Molesey Mystery (Inspector Lestrade’s Case. He handled it fairly well.)

“The Adventure of the Norwood Builder”

• The case of the papers of ex-President Murillo

• The shocking affair of the Dutch steamship, Friesland, which so nearly cost both Holmes and Watson their lives

• That terrible murderer, Bert Stevens, who wanted Holmes and Watson to get him off in ’87

“The Adventure of the Dancing Men”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist”

• The peculiar persecution of John Vincent Harden, the well-known tobacco millionaire

• It was near Farnham that Holmes and Watson took Archie Stamford, the forger

“The Adventure of the Priory School”

• Holmes was retained in the case of the Ferrers Documents

• The Abergavenny murder, which is coming up for trial

“The Adventure of Black Peter”

• The sudden death of Cardinal Tosca – an inquiry which was carried out by him at the express desire of His Holiness the Pope

• The arrest of Wilson, the notorious canary-trainer, which removed a plague-spot from the East-End of London.

“The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Six Napoleons”

• The dreadful business of the Abernetty family, which was first brought to Holmes’s attention by the depth which the parsley had sunk into the butter upon a hot day

• The Conk-Singleton forgery case

• Holmes was consulted upon the case of the disappearance of the black pearl of the Borgias, but was unable to throw any light upon it

“The Adventure of the Three Students”

• Some laborious researches in Early English charters

“The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez”

• The repulsive story of the red leech

• . . . and the terrible death of Crosby, the banker

• The Addleton tragedy

• . . . and the singular contents of the ancient British barrow

• The famous Smith-Mortimer succession case

• The tracking and arrest of Huret, the boulevard assassin

“The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter”

• Henry Staunton, whom Holmes helped to hang

• Arthur H. Staunton, the rising young forger

“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange”

• Hopkins called Holmes in seven times, and on each occasion his summons was entirely justified

“The Adventure of the Second Stain”

• The woman at Margate. No powder on her nose – that proved to be the correct solution. How can one build on such a quicksand? A woman’s most trivial action may mean volumes, or their most extraordinary conduct may depend upon a hairpin or a curling-tong

The Hound of the Baskervilles

• That little affair of the Vatican cameos, in which Holmes obliged the Pope

• The little case in which Holmes had the good fortune to help Messenger Manager Wilson

• One of the most revered names in England is being besmirched by a blackmailer, and only Holmes can stop a disastrous scandal

• The atrocious conduct of Colonel Upwood in connection with the famous card scandal at the Nonpareil Club

• Holmes defended the unfortunate Mme. Montpensier from the charge of murder that hung over her in connection with the death of her stepdaughter Mlle. Carere, the young lady who, as it will be remembered, was found six months later alive and married in New York

The Valley of Fear

• Twice already Holmes had helped Inspector Macdonald

His Last Bow

“The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge”

• The locking-up Colonel Carruthers

“The Adventure of the Red Circle”

• The affair last year for Mr. Fairdale Hobbs

• The Long Island cave mystery

“The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans”

• Brooks . . .

• . . . or Woodhouse, or any of the fifty men who have good reason for taking Holmes’s life

“The Adventure of the Dying Detective”

NONE LISTED

“The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”

• Holmes cannot possibly leave London while old Abrahams is in such mortal terror of his life

“The Adventure of the Devil's Foot”

• Holmes’s dramatic introduction to Dr. Moore Agar, of Harley Street

“His Last Bow”

• Holmes started his pilgrimage at Chicago . . .

• . . . graduated in an Irish secret society at Buffalo

• . . . gave serious trouble to the constabulary at Skibbareen

• Holmes saves Count Von und Zu Grafenstein from murder by the Nihilist Klopman

The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes

“The Adventure of the Illustrious Client”

• Negotiations with Sir George Lewis over the Hammerford Will case

“The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier”

• The Abbey School in which the Duke of Greyminster was so deeply involved

• The commission from the Sultan of Turkey which required immediate action

• The professional service for Sir James Saunders

“The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone”

• Old Baron Dowson said the night before he was hanged that in Holmes’s case what the law had gained the stage had lost

• The death of old Mrs. Harold, who left Count Sylvius the Blymer estate

• The compete life history of Miss Minnie Warrender

• The robbery in the train de-luxe to the Riviera on February 13, 1892

“The Adventure of the Three Gables”

• The killing of young Perkins outside the Holborn Bar

• Mortimer Maberly, was one of Holmes’s early clients

“The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire”

• Matilda Briggs, a ship which is associated with the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared

• Victor Lynch, the forger

• Venomous lizard, or Gila. Remarkable case, that!

• Vittoria the circus belle

• Vanderbilt and the Yeggman

• Vigor, the Hammersmith wonder

“The Adventure of the Three Garridebs”

• Holmes refused a knighthood for services which may, someday, be described

“The Problem of Thor Bridge”

• Mr. James Phillimore who, stepping back into his own house to get his umbrella, was never more seen in this world

• The cutter Alicia, which sailed one spring morning into a patch of mist from where she never again emerged, nor was anything further ever heard of herself and her crew.

• Isadora Persano, the well-known journalist and duelist who was found stark staring mad with a match box in front of him which contained a remarkable worm said to be unknown to science

“The Adventure of the Creeping Man”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane”

NONE LISTED

“The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger”

• The whole story concerning the politician, the lighthouse, and the trained cormorant

“The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place”

• Holmes ran down that coiner by the zinc and copper filings in the seam of his cuff

• The St. Pancras case, where a cap was found beside the dead policeman. Merivale of the Yard, asked Holmes to look into it

“The Adventure of the Retired Colourman”

• The case of the two Coptic Patriarchs

It's possible that a few more Untold Cases are mentioned in The Canon than are listed here, and possibly others can be teased out by interpreting Watson's writings in a new way. (If you see any that I've missed, please let me know!) Luckily for all of us, the Tin Dispatch Box holds many adventures, and is nowhere near being empty.

©David Marcum 2019 – All Rights Reserved

*************************

David Marcum plays The Game with deadly seriousness. He first discovered Sherlock Holmes in 1975 at the age of ten, and since that time, he has collected, read, and chronologicized literally thousands of traditional Holmes pastiches in the form of novels, short stories, radio and television episodes, movies and scripts, comics, fan-fiction, and unpublished manuscripts. He is the author of over 140 Sherlockian pastiches, some published in anthologies and magazines such as The Strand, and others collected in his own books, The Papers of Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock Holmes and A Quantity of Debt, and Sherlock Holmes – Tangled Skeins, and The Collected Papers of Sherlock Holmes, now at eight massive volumes (and counting). He has edited over 1,300 Holmes stories, and also 110 books, most of which are traditional Sherlockian anthologies, such as The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories, which he created in 2015. This collection finished in 2025 with 52 volumes and over 1,000 stories, having raised over $165,000 for the Undershaw school for special needs children, located at one of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's former homes.

He was responsible for bringing back August Derleth’s Solar Pons for a new generation, first with his collection of authorized Pons stories, The Papers of Solar Pons, along with The Further Papers of Solar Pons and The Singular Papers of Solar Pons, and then by editing the reissued authorized versions of the original Pons books. He has the same for the adventures of Dr. Thorndyke and Max Carrados. He has contributed numerous essays to various publications, and is a member of the Mystery Writers of America, along with a number of Sherlockian groups and Scions. His stories have appeared in many anthologies and magazines, including The Strand and Best Mysteries of the Year 2021, edited by Lee Child and Otto Penzler. Lee Child has said that "Marcum could be today's greatest Sherlockian writer . . . ."

He is a licensed Civil Engineer, living in Tennessee with his wife and son. His irregular Sherlockian blog, A Seventeen Step Program, addresses various topics related to his favorite book friends (as his son used to call them when he was small), and can be found at http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/ Since the age of nineteen, he has worn a deerstalker as his regular-and-only hat. In 2013, he and his deerstalker were finally able make his first trip-of-a-lifetime Holmes Pilgrimage to England, with return Pilgrimages in 2015 2016, 2024, 2025, where you may have spotted him. Another is planned in a couple of years. If you ever run into him and his deerstalker out and about, feel free to say hello!

His Amazon Author Page can be found at:

https://www.amazon.com/kindle-dbs/entity/author/B00K1IKA92?_encoding=UTF8&node=283155&offset=0&pageSize=12&searchAlias=stripbooks&sort=author-sidecar-rank&page=1&langFilter=default#formatSelectorHeader

and at MX Publishing:

https://mxpublishing.com/search?type=product&q=marcum&fbclid=IwAR12tH4SUvE9nmEnnuqeI5GC7Tv69-NagPgmAZlxcz0vr2Ihza5_6jP-fXM

Occasional ponderings about Sherlock Holmes, and maybe a few other things from time to time.

Friday, November 29, 2019

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Watson’s Wives and A Question of Chronology

[A version of this essay originally appeared in Volume 7, Issue 1 (June 1st, 2019) of Proceedings of the Pondicherry Lodge, the official journal of The Sherlock Holmes Society of India, edited by Jayantika Ganguly]

The question of Dr. Watson’s wives has been addressed elsewhere in countless scholarly inquiries. Although there will never be agreement – because agreement in Sherlockiana is as common as when it occurs in religion or politics – there are some theories – such as the one where the Good Doctor has seven (or more) wives – that can be politely ignored as a waste of time.

The Canon mentions two definitive wives: Mary Morstan, whom Watson met in September 1888 during The Sign of Four, and the unnamed woman that Watson married in the latter half of 1902. More about them in a bit.

There are a number of Canonical cases that occur in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s, during the period when Watson was married. Typically, chronologicists disagree on Sherlockian dates in the same way that two economists will have three opinions. Still, there are some cases that are more specific in terms of dating – and these cause problems when trying to decide whether or not Watson was married when a certain narrative occurs, and if so . . . was he married to Mary?

QUESTIONS OF CHRONOLOGY

Dates are sometimes firm in The Canon, sometimes not so much, and sometimes even a firm date can be shredded. In “The Red-Headed League”, Watson says that he had called upon Holmes “one day in the autumn of last year”. Since this adventure was published in The Strand in August 1891, most chronologicists place it in 1890. (This year is later confirmed in the story.) But then it gets tricky. Watson said it was “in the autumn”. And yet, in regard to publication of the first advertisement for the League, Watson says: “It is The Morning Chronicle of April 27, 1890. Just two months ago.” April is not two months ago from October. Jabez Wilson then reports that eight weeks pass from his initial interview and hire with the League to that same morning, when he decides to visit Holmes, after discovering this notice:

The Red-Headed League

is

Dissolved

Oct. 9, 1890

A Closer Look . . . .

For a Sherlockian chronologicist, this ought to be pure gold: An actual firm date as a jumping-off place. REDH occurred on October 9, 1890 – curiously rendered in the American form of month before day, even in the original Strand version (see illustration). This confirms that it did occur a year ago from the 1891 publication, and October is definitely in autumn.

But . . . the events of the story clearly take place on a Saturday – in fact, they have to occur on a Saturday to make sense – and October 9, 1890 is a Thursday! So our solid date, the one fixed point we can grab when trying to date this case, is ephemeral.

That throws the whole thing open to interpretation or adjustment. All of the major chronologicists still agree that REDH occurs in October, and most – but not all – still put it in 1890. But in October 1890, some favor October 4th, or 11th, or the 18th – all Saturdays, but not October 9th. Brend will only say October 1890 without picking a specific day. Others choose different years – Baring-Gould 1887 and Zeisler 1889 – and even then, they don’t set it on October 9th, instead picking October 29th or October 19th respectively, because both are Saturdays.

And what to do about that pesky April reference when Jabez Wilson was initially hired, eight weeks before his visit to Holmes? It can’t have been April as listed, but it could have been August. That fits, and the realization that someone – The typesetter at The Strand? The Literary Agent? – mis-read Watson’s notes, perhaps taking the abbreviation Au for Ap, becomes the most likely explanation for this inconsistency.

While this might seem to have little to do with Watson’s Wives, this is the kind of question that fascinates and vexes The Holmesian Chronologicist – and it’s these same kinds of matters that lead to questions about how many times that Watson was married, and to whom.

A TIME WHEN THE DATES DIDN'T MATTER . . . .

I first discovered The Canon in 1975, at the age of ten. I read the adventures out of order, in whatever order that I could obtain them. For instance, I was with Holmes and Watson in “The Empty House” weeks before I ever owned a copy of The Memoirs, or read “The Final Problem”. Thus, I knew that Holmes had survived his battle with Professor Moriarty atop the Reichenbach Falls, and exactly how he did it, before I ever realized that he was believed to have died in the first place. I was ten years old, and Canonical dates were just noise to me then – I wanted to read about what my Heroes were doing, not when they were doing it.

But not long after discovering The Canon, it was time to make my yearly Christmas list, and I looked through a book catalogue that my dad regularly received. There, on the inside back page was a whole Sherlock Holmes section – more titles than I could possibly request - even from my parents who brilliantly supported my love of reading and the need to have more books. At that time, I was pretty much only reading two things, The Three Investigators (the best) and The Hardy Boys (a close second), and the brilliant publisher marketing always included lists of the other books in the series on the back cover of each book. Acquiring those books and checking them off the lists were the early sparks that lit the fires of being a collector, and seeing that there were other books about this Sherlock Holmes chap, besides the nine original volumes, was very interesting to me.

I asked for several of the titles in the catalogue that Christmas, including The Sherlock Holmes Companion (1972) by the Michael and Mollie Hardwick, The Sherlock Holmes Scrapbook (1974) by Peter Haining, a set of old Rathbone radio shows from Murray Hill Records . . . and Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street (1962) by William S. Baring-Gould.

Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street changed everything, because reading it took me from simply racing through each Holmes adventure to actually thinking about each adventure, and how it fit with the others, and more importantly, how it fit within the context of Holmes and Watson’s entire lives. Now I was playing The Game. Now I was a Sherlockian.

From that point, I became a Baring-Gouldist as well, buying into many - but not all - of the ideas that he presented in Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street. This was only reinforced a few years later when I received the amazing boxed set of his Annotated Sherlock Holmes as a birthday gift.

Of course, I don’t blindly agree with everything that Baring-Gould described. His above-mentioned dating of REDH to 1887, for instance, is a pure mistake, contradicted by the very Canon. Likewise, he puts “The Resident Patient” in 1886 – although to be fair, most major chronologicists get this one wrong, too, with most of them placing it in 1887, or a few in 1882 or 1886. If one goes back and reads the original Strand version, before the odd publication history and text changes of “The Cardboard Box” caused it to lose its original opening, Watson clearly states “I cannot be sure of the exact date, for some of my memoranda upon the matter have been mislaid, but it must have been towards the end of the first year during which Holmes and I shared chambers in Baker Street.” (For more about the correct RESI text, see The Oxford Sherlock Holmes – The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes pp. 174 and 306-307.)

Even though Baring-Gould misses the mark on some things, he gets others very right. The revelation of the existence of Sherrinford Holmes as Mycroft and Sherlock’s older brother, for example. I completely and absolutely accept The Meeting in Montenegro between Holmes and Irene Adler, as originally theorized by others but codified by Baring-Gould, and the amazing result of that meeting, leading to my second-favorite book friend after Holmes. I agree with his dating of some of the cases – especially those that are in question because of contradictory statements within the narratives about Watson’s marriages and the times when they occur. And by way of this, Baring-Gould gives us information about Watson’s first wife, Constance.

SHIFTING DATES

In The Sign of the Four, we meet Mary Morstan, the only wife in The Canon whose name is known to us. She begins her story by stating that “[a]bout six years ago – to be exact, upon the 4th of May, 1882 – an advertisement appeared in The Times . . . .” Thus, we can decide with some confidence that this case occurs in 1888, six years after 1882. So far so good? Not so fast . . . .

A few lines later, Mary reveals a letter that she received that morning. “The envelope too, please,” says Holmes. “Postmark, London, S.W. Date, July 7. Hum!” So we can then decide that SIGN begins on July 7th, right? Hold on. In the next chapter, Watson says, “It was a September evening.” July? September? Huh? What? Wait – What to do? My thinking is that Watson’s notes had a 9 written for the month, and it looked too much like a 7. Some major chronologicists (Baring-Gould, Christ, Dakin) go with September 1888 as the date of this adventure, while Blakeney, Brend, and Folsom choose July 1888. Inexplicably, Bell chooses September 1887, and Zeisler likes April 1888. (I favor September 1888 in my own extensive and massive chronology of both Canon and Pastiche, which I started in the mid-1990’s, now numbering around one-thousand densely packed pages. For more about The July-September Question, see Note 14, p.124 in The Oxford Sherlock Holmes edition of The Sign of the Four.)

Actually, there are other reasons that Bell likely chose September 1887. He’s trying to explain contradictory references in “A Scandal in Bohemia” and “The Five Orange Pips. In SCAN, Watson states “. . . it was on the twentieth of March, 1888 . . . .” A solid date upon which to build, one would think – until one recalls that naming a specific date in The Canon can often be like making bricks without clay. For what follows this line is the recounting of Watson’s visit to 221b Baker Street just after his marriage, and a discussion about how marriage suits him. But wait . . . . . If Watson met Mary Morstan in 1888 – either July or September – then how is he already married in March 1888?

Likewise, in FIVE, the case is said to occur in September 1887. (However, only Baring-Gould and Hall accept that, with Blakeney, Christ, Dakin, Folsom, and Zeisler shifting it to September 1889, and Bell and Brend moving it to September 1888. At least they could all agree on September.) Along with this September 1887 date, a year before Watson meets Mary Morstan, he also states that he’s temporarily staying in Baker Street because “My wife was on a visit to her mother’s . . . .” Yet how can this be Mary Morstan that he’s discussing? She stated in SIGN, when introducing her problem to Holmes, that she was sent home from India as a child years before meeting Watson, and that at that time her mother was dead! Clearly, this woman to whom Watson is married in 1887, before he meets Mary Morstan in September 1888, is another wife – a first wife!

Tangentially related to this problem is the dating of The Hound of the Baskervilles. At the very beginning of the tale, Dr. Mortimer’s stick is shown to have been engraved in “1884”. Just a few lines later, Holmes indicates that the engraving marked an event “five years ago” – thus placing HOUN in 1889 – or so one would believe. Of course the chronologicists disagree. Only Blakeney and Hall actually say that it occurs in 1889. Bell puts it in 1886, Christ in 1897, and Dakin, Folsom and Zeisler in 1900. (How do they get 1900 as being five years after 1884?)

Why do so many of these scholarly chronologists feel the need to shift the story from the implied 1889 date? It’s because of the fact that Watson is already supposed to be married by then, having met Mary Morstan in September 1888, and logically having wed her sooner rather than later. So if he’s married by then, in autumn 1889, why is he still living in Baker Street – and more importantly, how is he able to go with Sir Henry Baskerville to Dartmoor for weeks and weeks at the drop of a hat? Possibly that tried-and-true device of having Watson’s wife away visiting someone and the good doctor is staying indefinitely in his old Baker Street rooms might be the explanation – except he certainly has a medical practice to maintain after his marriage, as mentioned in “The Engineer’s Thumb”, for example – and how would he walk away from that, simply to vanish into the Dartmoor wilderness for such a long a period of time?

The chronologicists solve this problem by shifting HOUN to a period when Watson was not married – and therefore he has no wife from whom to walk away. Baring-Gould answers both the SCAN and HOUN time-frame marriage problem in his own way. He shifts HOUN back to 1888, occurring not long after SIGN. Moving a case is not frowned upon by chronologicists, who recognize that a number of Canonical dates are incorrect, either due to Watson’s carelessness, his intentional obfuscation of facts, his poor handwriting, the shoddy effort by typesetters, or even some dark and sinister motive of the Literary Agent, who likely had his own agenda to cruelly foist upon Watson's notes. Some cases absolutely have to be time-shifted, as in “Wisteria Lodge”, which begins on “a bleak and windy day towards the end of March in the year 1892.” But at the end of March 1892, as we all know, Holmes was believed to have died at the Reichenbach Falls nearly a year before, and in fact he was nearly one-third of the way through The Great Hiatus. There’s simply no way that he and Watson were in London carrying out a routine investigation in March 1892. This is clearly a misprint or an obfuscation – and the perfect example of why Canonical dates cannot be trusted, and can be adjusted.

With HOUN shifted to 1888 in Baring-Gould’s chronology, occurring not long after Watson meets Mary, there is no marriage or practice yet to conflict with his West Country mission. This period, with SIGN and HOUN, was a very busy time for Holmes and Watson. Not to be ignored during this period was Holmes’s greatest investigation, that of The Ripper. I go more into depth about that in my essay “Sherlock Holmes versus Jack the Ripper”, which originally appeared in The Watsonian Fall 2015 (Vol. 3, No.2), and later as an entry from my blog:

http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/2017/02/sherlock-holmes-versus-jack-ripper.html

In the case of SCAN, where Watson is married before meeting Mary Morstan, Baring-Gould shifts the dates back one year, to March 1887. Some would argue that move places it outside of the possibility of being married to Mary – and they would be right. But it does set the story within the range of Watson’s first marriage.

WATSON'S FIRST MARRIAGE

Postulation of an earlier marriage helps to solve some of these chronological problems. Additionally, it smooths a few edges – although not all of them – with the facts related in Angels of Darkness, a play by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle that includes some aspects of Watson’s life, without any mention of Sherlock Holmes. (The play, long suppressed by the Doyle Estate, is available both from The Baker Street Irregulars and as a part of Les Klinger’s The Sherlock Holmes Reference Library: Volume X: The Apocrypha of Sherlock Holmes:

In it, Watson is a doctor in San Francisco, where he loves Lucy Ferrier, a name familiar to readers of A Study in Scarlet. Clearly, this is wrong, and for Watson to actually woo Lucy Ferrier sets up problems that cannot be explained away. The truth of the matter is that, during those mid-1880’s days when Conan Doyle and Watson were first working out the details of their literary arrangement, and figuring out what to write, it was decided that Watson would write the portion of A Study in Scarlet relating to Holmes’s investigation, and Conan Doyle, the budding historical novelist, would work up the Utah section, which so bogs the action of the rest of the book. (I realize that Conan Doyle is revered as a writer, but as the central historical section of STUD is one of the few examples of his writing that I’ve ever read, along with the middle part of The Valley of Fear and his introduction to The Casebook, I don’t judge him too positively.) In the process of creating this Utah segment, Conan Doyle decided to write a play about Watson’s time spent in San Francisco (as described in Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, where Watson traveled to California in order to assist his wayward brother.) In expanding upon this idea, Conan Doyle changed names, using several from the Utah section of STUD to litter Angels of Darkness. Therefore, the woman that Watson met in San Francisco was given the same name as the girl from the historical section of STUD. Watson, upon being shown the manuscript, was not amused, and Angels of Darkness was promptly shelved. Still, some authentic facts from it may be gleaned. Watson did spend time in San Francisco, and it was there that he met his first wife, who in truth was named Constance Adams.

For those who question Baring-Gould’s information about this and other assertions, it must be recalled that his grandfather, Sabine Baring-Gould, was Sherlock Holmes’s godfather. This has been confirmed by a separate source, as related in The Moor (1998), written by Mary Russell, and edited by Laurie R. King.

Much that Russell herself writes is highly questionable, as she was doing so from a perspective of spiraling mental illness, as outlined in “Necessary Rationalizations: The Overall Chronology of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson (along with the Truth About Mary Russell)", originally in The Watsonian (2017, Vol. 5, No. 1) , and later in an entry from this blog:

http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/2018/08/necessary-rationalizations-overall.html

Still, the fact that Sabine Baring-Gould was Holmes’s godfather explains a great deal about how his grandson William was able to obtain such specific and mostly correct information concerning Holmes and Watson for his biography, Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street – including details about Watson’s first wife, Constance.

We don’t know much about Constance. There have been a number of extra-Canonical stories that describe the time after she died, such as a few of mine, and also various stories in the Imagination Theatre radio broadcasts, which thankfully and specifically mention Constance by name. The events of their marriage are described in Chapter 7-10 of Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street. Watson first met her in San Francisco when he traveled there to help his poor brother. The most information that has otherwise been provided so far about the poor Constance Watson has been through “A Ghost from Christmas Past”, brought to us from Watson’s original notes by Tom Turley. (This story can be found in Part VII – Eliminate the Impossible: 1880-1891 of The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories, 2017)

In this narrative is a description of Watson and Constance’s courtship, as well as their subsequent move to England following their marriage on November 1st, 1886. After that, Constance became ill, and was forced to travel a great deal away from London, seeking better climes in which to heal. Watson, in the meantime, was forced to stay in London, attempting to build his practice so that one day he and Constance could afford to go elsewhere. It was during this period that he was able to continue his extensive involvement with many of Holmes’s cases, as later chronicled in a number of narratives that were presented to a world starving for more Holmes adventures by someone else than the original Literary Agent.

When Constance unexpectedly died just a few days after Christmas, 1887, just a little over a year after their marriage, a devastated Watson sold his practice and returned to Baker Street. The first months back were a grief-stricken adjustment, and it was during this time that Holmes, in order to help him work through his pain, began to relate a number of previously untold cases, such as “The Musgrave Ritual”, “The Gloria Scott”, “The Old Russian Woman”, “The Aluminium Crutch”, and many others. Through this period immediately following Constance’s death, Watson participated in a number of investigations as well, including the events of The Valley of Fear, and a couple that I’ve brought forth, including Sherlock Holmes and A Quantity of Debt (2013) and the forthcoming Sherlock Holmes and The Eye of Heka.

[Interestingly, I floated The Eye of Heka past a publisher – no names need be given, but they produce a fair amount of Sherlockian content, sold online and in bookstores ‘round the world, and they are a Giant in the business. The editor at the time – who no longer works there – was quite rude and arrogant, acting as if I had been a Holmes fan for maybe one week and had only read one Holmes story, likely my very first ever, and that I'd just had spontaneously decided to write a book. When I explained that The Eye of Heka was set in January 1888, immediately after the death of Constance, Watson’s first wife, she snidely informed me that they followed The Klinger Timeline, as developed by Les Klinger, and therefore nothing related to Constance was allowed. I was happy to point out to this now-no-longer-employed editor at the Giant publisher that Constance is mentioned three times - twice by name – in Mr. Klinger’s Chronology (see 1884, 1886, and 1887) – a fact that this editor hadn’t bothered to determine before referencing it, proving that this editor was moving in deep waters.

This chronology is available in Mr. Klinger’s Reference Library, published by Gasogene Books, an imprint of the Wessex Press.]

Throughout the early part of 1888, Watson never believed that he would marry again. But that autumn, he met Mary Morstan, and several months later, on May 1st, 1889, she became The Second Mrs. Watson. Mary has been portrayed a number of times on-screen, and a few times in print, including (Top to Bottom, Left-to-Right):

Jenny Seagrove (1987, Jeremy Brett as Holmes); Cherie Lunghi (1983, Ian Richardson as Holmes); Lynn Rainbow (1983, Animated , Peter O’Toole as Holmes); Sophie Loraine (2000, Matt Frewer as Holmes); Isla Bevan (1932, Arthur Wontner as Holmes); Isobel Elsom (1923, Eille Norwood as Holmes); Kelly Reilly (2009, Robert Downey Jr. as Holmes); Ann Bell (1968, Peter Cushing as Holmes); as illustrated by Richard Gutschmidt in Das Zeichen der Vier, 1902-1904; and by an unknown artist in Harper’s Magazine, 1904

Mary and Watson appear to have been quite happy, and a great number of extra-Canonical adventures tell of the few years that they were married. But Mary’s health was not-so-great, and sometime during The Great Hiatus, she passed away. There have been a number of reasons given in quite a few of the non-Literary-Agented narratives, but it seems to have been from a combination of many causes, including a carriage accident, combined with a plethora of ongoing illnesses, including tuberculosis, cancer, complications from past miscarriages, heart problems, a recent fall, and grief from the recent deaths of both a son and a daughter. Additionally, there have been many theories as to when her death occurred – either soon after Holmes was believed to have died on May 4th, 1891, or just before his return on April 5th, 1894, or anywhere in between. Personally, for my own Chronology, I’ve settled, after an examination of many sources, on April 27th, 1893 as the most likely date.

During the period immediately following Holmes’s presumed death, Watson began to chronicle a number of his adventures in short form. These were published between 1891 and 1893 in a brand new magazine, The Strand, which had only gone into business in January 1891. (For those pulling new adventures from Watson’s Tin Dispatch Box, Beware! Having Watson publish in The Strand before January 1891, in a time prior to its very existence, is a serious error!)

These initial twenty-four adventures were later collected into The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs. As described by Baring-Gould in Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, Watson was faced with a dilemma. Throughout most of the time he was compiling these stories for The Strand, Mary was still alive. How could he tell stories about Holmes from when Constance was still alive without hurting Mary’s feelings? At the urging of the Literary Agent, Watson was vague, mentioning a wife without giving her name, and leaving the impression that he was referring to Mary, even for cases that occurred before he met her in September 1888, when he really meant Constance. Likewise, Watson added mentions of The Sign of the Four to some of the published pre-Mary cases, implying that the wife in those was Mary and not Constance. (And it didn’t hurt, probably according to the Literary Agent, to work in mentions of The Sign of the Four, first published in 1890, to various stories, as a reminder to enthused readers who might like to know that it was still available to anyone that enjoyed reading the stories in The Strand.)

With the publication of “The Final Problem” in December 1893, Watson settled into a bleak existence – widowed, and still coming to terms with the death of his best friend. But he was mightily surprised in early April 1894 when Holmes returned to London, after it was thought that he’d never be seen again. Holmes had learned of Watson’s sad bereavement, and his sympathy was shown in his manner rather than in his words. “Work is the best antidote to sorrow, my dear Watson,” he’d said, and he invited the doctor to return to Baker Street, as he had in early 1888 following Constance’s death.

THE THIRD MRS. WATSON

After his return to 221b Baker Street in mid-1894, Watson lived there until after the turn of the century. Then we find an indication that change was in the wind. “The Illustrious client” begins on September 3, 1902. How do we know this? Because Watson writes that it was on “September 3, 1902, the day when my narrative begins.” With that in mind, it’s no wonder that two chronologicists, Folsom and Hall, state that it actually begins on October 3, 1902, while two others, Bell and Zeisler, shift it to September 13, 1902.

In any case, Watson states soon after that, “I was living in my own rooms in Queen Anne Street at the time . . . .” If he had moved out, there was likely a reason, and we find the most likely one described by Sherlock Holmes in “The Blanched Soldier”, which occurs in January 1903. (Amazingly, every major chronologicist actually accepts this date – maybe because Holmes himself states it - unlike Watson and his questionable chronological assertions, Holmes has given us no reason to doubt!)

In BLAN, Holmes writes, “I find from my notebook that it was in January, 1903, just after the conclusion of the Boer War . . . The good Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife, the only selfish action which I can recall in our association. I was alone.”

How markedly different is this hint about Holmes’s relationship with the 1902-1903 wife – Watson’s third – when compared to the mutual respect implied during Watson’s first and second marriages of the mid-1880’s and early 1890’s.

Although nothing else can be gleaned Canonical about Wife Number Three, she has made a number of appearances in extra-Canonical adventures – but under many different names, and exhibiting vastly differing backgrounds and personalities. These include:

• The Adventures of The Second Mrs. Watson (2000), Murder in the Bath (2004), The Exploits of the Second Mrs. Watson (2008), and The Stratford Conspiracy (2011) – Michael Mallory: Amelia Watson, née Pettigrew, a former actress in the theatre. In an email of May 16th, 2019, Mr. Mallory assures me that “Amelia will be back (after a bit of a hiatus) in issue #30 of Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, late 2019 or early 2020. She is now employed as an operative for Whitehall's M Division, headed by (you guessed it) Mycroft Holmes.” Even though she’s called the second Mrs. Watson, she’s the third – trust me . . . .

• Sherlock Holmes and the German Nanny (1990) – John North (whom I strongly suspect was prolific pasticheur Val Andrews): Watson is being pursued by Tilly Footage, who is working as his receptionist, but he hasn’t married her yet. (Several other volumes published by Ian Henry in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s also include Tilly, although a reference to her being the Third Mrs. Watson isn’t mentioned. These various books are purported to come from The Footage-Watson Papers.)

• Sherlock Holmes and the Arabian Princess (1990) – also John North (This same story was first published as a musical comedy script Sherlock Holmes and the Deerstalker 1984): At the conclusion, Watson is going to marry a showgirl named Tilly Footage.

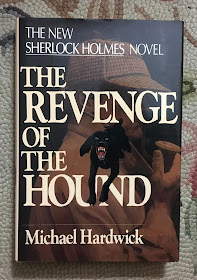

• The Revenge of the Hound (1987) – Michael Harrison: Set in the summer of 1902, in and around the events of “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”, Watson is engaged to Coral Atkins:

• “The Adventure of the Marked Man” is in both The Game is Afoot (1994) and also The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1985) – Stuart Palmer: Watson’s fiancé is Signora Emilia Lucca of “The Red Circle” . . . .

• Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Silk Stocking (Film, 2006): Watson’s fiancé is an American psychologist named Mrs. Vandeleur – curiously the same name as one of Stapleton’s aliases in The Hound!?!?

• "The Adventure of the Russian Grave" in Sherlock Holmes in Orbit (1995) - William Barton and Michael Capobiano: An example of one of the may post-1902 adventures that mention Mrs. Watson but don't give her name.

• “The Illustrious Client” (BBC Radio Version, September 21, 1994 Dramatized by Bert Coules): Watson’s fiancé is named Jean, and in. . . .

• “The Mazarin Stone” (BBC Radio Version, October 5, 1994, Dramatized by Bert Coules) . . . In these, Watson’s wife is named Jean. (Bert Coules has said that this was in honor of Jean Leckie Doyle)

• “The Adventure of the Mocking Huntsman” [Sherlock Magazine #55, 2003] and in an alternate form as “The Covetous Hunstman” in The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Imagination Theatre Radio Broadcast No. 51, July 25, 2004,) both versions presented by Matthew Elliott: In “The Mocking Huntsman” Watson’s wife isn’t named, but the story indicates that she has a grown son named Elias who is a part-owner in an automobile factory. In “The Covetous Huntsman”, her name is given as Kate.

• “The Adventure of the Second Generation” (Radio Broadcast, December 17th, 1945, dramatized by Denis Green and Anthony Boucher) and also in The Lost Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (transcribed by Ken Greenwald): In the text version, Watson’s wife is named Anna. She was killed in a four-wheeler accident not long before this narrative.

• Sherlock Holmes and the Lusitania (1999) – Lorraine Daly: Watson is married to Violet Hunter of “The Copper Beeches”.

• The Seventh Bullet (1992) – Daniel D. Victor: An unnamed wife who has never been to America.

• Nightwatch (2001) – Stephen Kendrick: Watson is engaged to an unnamed nurse-in-training that he met at Barts.

• “The Canaveral Caper” in Indian River Trilogy (1989) – Donald W. Holmes: Watson’s 1902-1903 third wife is also named Mary.

• The Adventure of the Peerless Peer (1974) – Philip Jose Farmer: Watson is married to a native girl that he and Holmes rescued in Africa during World War I – not quite the 1902-1903 wife, but still a later wife worth mentioning . . . .

• “Sherlock Holmes and the Mysterious Card” (1999) – Joel Lima: Watson’s wife is named Violet, the daughter of a general. (I’ve wondered if it’s implied that Watson married Violet de Merville, General de Merville’s daughter, from “The Illustrious Client”?)

And finally, the most recent portrayal of The Third Mrs. Watson is in Nicholas Meyer's The Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols (2019): Watson is married to the former Juliet Garnett, the sister of writer, critic, and editor Edward Garnett (1868-1937).

IN CONCLUSION . . . .

There is far more about this topic than could ever be discussed in this short essay – both in terms of scholarship examining Watson’s wives, and specific discussion of all the times that the various wives have appeared in both the Canon (on-stage or implied) or in extra-Canonical adventures brought to us without having to first cross the Literary Agent’s desk.

Some may give no thought to Watsonian Wives or Sherlockian Chronology, instead racing through the adventures like I did as a ten-year-old, new to The Canon, and totally oblivious to these deeper questions. But for those who do enjoy drilling deeper, there is a never-ending joy in seeing the connections and hints and clues, and how it all fits together. There is plenty of clay there for those willing to make the effort to make the bricks.

©David Marcum 2019 – All Rights Reserved

*************************