Discovering Hercule Poirot

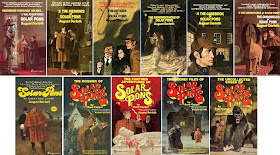

I first became aware of M. Poirot in the fall of 1978, when the film Death on the Nile was released. I was thirteen, and had been a developing mystery fan for about five years, although my exposure to the genre was still quite limited. I had discovered mysteries by way of the excellent series The Three Investigators – nominally for children, but still amazingly readable as an adult. From that, I pivoted to The Hardy Boys – there were a lot more of those to enjoy and collect, but sadly, the plotting and writing just don’t hold up nearly as well from a grown-up perspective. At the age of eight, I had discovered just a tiny bit about Solar Pons, the Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street, and then at ten, in 1975, I found Mr. Sherlock Holmes himself, and never looked back.

From then to now, Sherlock Holmes has been my greatest hero – but certainly not the only one. In the years immediately following my initiation into the Holmesian World, I began to encounter a few of the other greats. First was Ellery Queen, another sleuth that I avidly admire and advocate to the present day. The next was Hercule Poirot.

In 1978, someone in my hometown had remodeled and reopened a tiny theater on our main street that had been there since the 1930’s. (Or perhaps even earlier. It’s still there, and in the intervening years it’s closed and reopened again any number of times. One of my lottery daydreams is to buy it – it’s for sale again right now – and make the upstairs into a writing office and show the movies that I like on the ground floor.) Back on that autumn 1978 evening, I had seen in the newspaper that Death on the Nile was playing, and I convinced my dad to take me.

Mysteries weren’t exactly his thing – he loved history and John Wayne-type movies and Big Band music – but he and my mom were incredibly encouraging regarding all of my interests, and they especially supported my love of reading and then collecting books. So he and I went to the movie, and found ourselves alone in the small narrow theater. It’s one of my favorite memories, the two of us there, carried away to another world. And through that singular experience, my enjoyment of mysteries was elevated to a new level.

This film was epic in scope, filmed on location in Egypt, and with a cast of major stars. At that time, I hadn’t ever read a Hercule Poirot story, and I can’t recall if I even knew anything about him at all before seeing Peter Ustinov’s portrayal. I was to learn later just how incorrect Ustinov was in the part – he was a big sloppy-looking man without Poirot’s more diminutive neatness. (There is an anecdote that Agatha Christie’s daughter, Rosalind Hicks, saw Ustinov and observed that Poirot looked nothing like him. “He does now!” snapped Ustinov.)

What blew me away most with Death on the Nile was the story-telling technique that I hadn’t yet encountered – the famed gathering of the suspects at the end, with a neat recounting, person by person, by the all-knowing detective of how the events of the crime occurred, illustrated by accompanying flashbacks that actually showed what had happened and how all the crazed pieces of the puzzle fit together.

I was stunned by the complexity of the plot, and also by that type of denouement. There was certainly nothing like that in the typical Holmes Canon – although in the years since, I’ve encountered any number of newer Holmes stories that do use that technique – and The Three Investigators and The Hardy Boys never unmasked the culprit in quite that way. I walked out of the theater that night with a whole new elevated hunger for mystery stories, and I credit watching that particular film for making me that much more receptive to Nero Wolfe and his similar unmasking of the criminals when I first encountered him a few years later, in early 1981.

For more about Nero Wolfe and Ellery Queen, see my related blogs:

“Re-reading the Nero Wolfe Adventures - A Visit to the Brownstone of Sherlock Holmes's Son”

http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/2016/01/re-reading-nero-wolfe-adventures-visit.html

and “Rereading The Ellery Queen Canon”

http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/2016/02/rereading-ellery-queen-canon.html

A few days after seeing the film, I located a used copy of the novel of Death on the Nile, and began the next step of my long foray into The World of Poirot. Now, thirty-nine years later, my admiration for the man and his “little grey cells” has only increased.

In the fall of 1982, when I was starting my senior year in high school, I became aware of Ustinov’s second portrayal of Poirot in Evil Under the Sun. Somehow I’d missed this in the theater, but it was being shown on HBO. Cable television had only recently come to my hometown, and I recall getting up early on a Saturday morning to watch it. I hadn’t read the book yet, so it was all a surprise to me. (As a side note related to this film: I’ve never ever seen an episode of The Avengers, and it was years before I saw the film version of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – I’m also a huge James Bond fanatic, but I luckily read the books and learned to appreciate the true James Bond before seeing all the ultimately not-quite-right films. Thus, my initial exposure to Diana Rigg wasn’t for her more famous roles, but rather in Evil Under the Sun and her portrayal of Arlena Stuart Marshall. This has completely colored my perception of her in other roles to this day, including that of Olenna Tyrell in Game of Thrones. But – as usual – I digress.)

I continued to read Poirot in a rather hit-or-miss fashion, and was happy to find that a couple of my friends in high school were also reading them. It was fun having the random discussion about what was possibly Poirot’s finest hour, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), or the surprise ending of Curtain (1975) – which I read out of order and long before many of the other Poirot titles.

As time passed, and I went to college, married, and found jobs, I paid attention when Ustinov’s four other Poirot outings were released, Thirteen at Dinner (1985), Dead Man's Folly (1986), Murder in Three Acts (1986) and Appointment with Death (1988). And as with all the other “Book Friends” (as my son later called them when he was small), I continued to collect and read material about Hercule Poirot. Luckily, the main books were easy to find, and one of the great treasures during that period was the massive hardcover release of the complete Poirot short stories in one giant volume, a Christmas gift one year from my dad.

Only later, when I was a more sophisticated collector, did I realize that the whole Poirot collection that I’d accumulated wasn’t quite complete, as there had been alternate versions of some Poirot stories released at different times in the past. A few of these were initially narrated by Poirot’s friend, Captain Arthur Hastings, only to be rewritten by Christie and republished at a later date in an updated setting, and with Hastings removed. Other Poirot stories were also later rewritten or expanded, with one eliminating Poirot entirely and changing the story to feature another Christie character. I’ve had a great deal of fun seeking out these original alternate or unknown “lost” Poirot stories.

Some of these altered stories include:

• “The Submarine Plans”, originally narrated by Hastings, and then republished without him as “The Incredible Theft”;

• “Christmas Adventure”, later revised as “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”;

• “The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest”, later revised as “The Mystery of the Spanish Chest”;

• “The Second Gong”, also originally with Hastings, and later revised as “Dead Man's Mirror”;

• “Poirot and the Regatta Mystery”, which became the Parker Pyne story, "The Regatta Mystery";

• “The Capture of Cerberus”, a completely alternate version of the same story published in The Labours of Hercules, (published posthumously);

• “The Incident of the Dog’s Ball” (published posthumously,) the original version of Dumb Witness (1956); and

• Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly (published posthumously,) the original version of Dead Man’s Folly (1937);

Although I haven’t read any of Christie’s stand-alone novels, such as And Then There Were None (1939), or the Tommy and Tuppence Beresford mysteries, or even anything (yet) about Miss Marple – although I do have all of that famous lady’s adventures and hope to read them someday – I do own and have read all of the books and stories featuring the friends and associates of Poirot, where they have appeared elsewhere without him. These include the non-Poirot titles (books and short stories) featuring Ariadne Oliver, Superintendent Battle, Colonel Johnny Race, and Miss Lemon.

Additionally, there have been a couple of volumes of “lost” Christies, edited by John Curran, that have been invaluable. Julian Symons included a wonderful chapter on Poirot in his amazing book Great Detectives (1981), and most recently, Sophy Hannah has Literary Agent-ed two previously unknown Poirot adventures, The Monogram Murders (2014) and Closed Casket (2016), and at least two more have been announced to follow in 2018 and 2020. Keep them coming!

Finally, I have high hopes for the re-release someday of the adventures of Jules Poiret and Captain Haven. [EDITORS'S NOTE - See Below - New information indicates that the Jules Poiret stories are a hoax.] Written in the early 1900’s by Frank Howell Evans, these stories, freely admitted by Christie to have been a strong influence on her Literary Agent-ing, have such Poirot similarities that they might almost be Poirot mysteries themselves under another name. Poiret and Haven reside in London, where Poiret functions as a consulting detective. For a while, the stories were for sale individually on Amazon, and to my everlasting regret, I waited too long before buying them, only to find that all of them that had been available, at one time over thirty, had been removed. Subsequent in-depth internet searches have failed to turn up any reprints in any other format, ever. One can only hope these Poiret adventures will once again be available at some point, and if anyone reading this has any way to bring the stories back to print, I urge you to do so.

[EDITOR'S UPDATE - March 18, 2019]: While I don't know the details, and will track them down for another update, apparently the whole Jules Poiret run of stories is a modern-day hoax, all written within the last few years, and with a completely false back-story implying that they've been around for nearly a century. I've tracked them down, and still plan to read them, but they are not what they say they are . . . .]

Poirot on Film

In my thirties, I went back to school to obtain a second degree in Civil Engineering. It was a long slog, and when I was finished, my collective family gave me a graduation present of cash money. I turned around and spent it on every Poirot DVD then in existence, a very satisfying stack of box sets, most of which starred David Suchet as the little Belgian detective.

In 1989, the Poirot mantle was assumed by David Suchet, who had almost forgettably played Inspector Japp in Ustinov’s Thirteen at Dinner (1985). (In Suchet’s excellent Poirot-related biographical memoir, Poirot and Me [2014], published the year after he played the role for the last time, he relates that when playing Japp, he had no clue regarding what to do, and in the end, he resorted to simply having Japp eating something in every scene.)

As each series of Poirot was broadcast, I was an avid follower. Suchet, in my opinion, is the closest that any actor will ever get to being Hercule Poirot.

He has the look, the walk, the accent, the intelligence, and the attitude – although he is missing Poirot’s notable green eyes, and one can’t blame him too much for that. Hugh Fraser is the perfect Arthur Hastings. Philip Jackson is perfect as Inspector Japp, and Pauline Moran is perfect as Miss Lemon. The filmed exteriors of Florin Court in Charterhouse Square, London, as Poirot’s later lodgings, Whitehaven Mansions, are perfect as well – although the real-life location of this building, far from the specified Mayfair location, is nowhere that Poirot would choose to live. (More about that in a moment.)

Of course, the television show made some changes. Many of the earlier original short stories have Poirot and Hastings sharing lodgings at the modest 14 Farraway Street, in a flat that, as described, is very similar in tone to Sherlock Holmes’s 221b Baker Street, and with a Mrs. Hudson-like landlady, Mrs. Murchison. In the Suchet television show, all of these early Farraway Street stories have been reworked to include Hastings and Miss Lemon – whether they were originally in them or not – and with Poirot already living in Whitehaven Mansions, a location where he would not move until after Hastings had married and moved to Argentina following the mid-1922 events of The Murder on the Links (1923). After that event, Hastings would only be irregularly involved in Poirot’s investigations during his visits back to England.

Another change to Poirot television series was the regular inclusion of Inspector Japp, who didn’t appear nearly as frequently in the books. A more unusual alteration is the implication in the television films that Hastings is, like Miss Lemon, Poirot’s employee, when in truth he was employed as the secretary of a Member of Parliament before his emigration from England. There were other times that the Suchet episodes veered considerably from the original stories, most noticeably on those occasions when the scripts that they used were completely new pastiches with only the same title in common with the original publication. (This, for instance, was quite evident in 1993’s “The Case of the Missing Will”.) Doing this was sometimes understandable, as some of those original stories were only a few pages long, making it necessary to flesh them out in order to have enough material to fill an entire episode.

Sometimes, however, these changes were done to my great disappointment. For instance, in 2013, toward the very end of Suchet’s run as Poirot, the stated goal was to film every Poirot story – although in fact a number weren’t actually filmed. (See below.) One set of tales that was saved for last was the excellent collection of twelve related stories, The Labors of Hercules (1947). This was condensed into one film, with only a few stories actually used and only mere nods as passing references to a number of others from the book. I realize that by then, the money was running out, and that a significant effort was likely required to convince The Powers That Be to financially fund making the final films, but this book should have been produced as its own twelve-episode series.

And then there is the matter of The Big Four (1927), which originally appeared as four related but separately written and published stories that were later refashioned by Christie into an epic novel – and one that is quite a bit different from the usual Poirot, being much more similar to a Sax Rohmer "Denis Nayland Smith" adventure than any previous (or since) Poirot books. The television version was scripted for a 2013 broadcast by Mark Gatiss, the man half-responsible for that most terrible and damaging of shows, the BBC Sherlock The Big Four is one of my favorite Poirot books, with its unusual plot, and the inclusion of Poirot’s nearly otherwise unmentioned brother, Achille. Unfortunately, Gatiss simply cut out the best parts. It isn’t the fault of Suchet or the other actors – they worked with what was given to them - but the anticipation that I felt for years while waiting to see this particular book filmed turned out to be particularly disappointing.

The Matter of Poirot’s Age

Suchet fittingly ended his run as Poirot with Curtain, correctly set (as shown in the episode) in 1949. Poirot’s age has long been debated, but I’m of the school of thought that Poirot lived to a normal old age before dying normally – and not exceeding a normal life-span to some magical sesquicentennial. (There are some who disagree - the same ones that also believe that Sherlock Holmes is still alive, out there somewhere, and that Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin never age. This is wrong.)

The confusion about Poirot’s age comes from the fact that he was described as retired and elderly in the first book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920). Therefore, people picture him already quite old by then, and then it's assumed that the stories must be occurring in real time – with Poirot getting even older along the way. Thus, when Curtain was published fifty-five years after the first book, in 1975, Poirot must have been quite old indeed. However, certain facts have to be considered when considering Poirot’s true age.

First, while Poirot was retired in 1916, when we first meet him in Essex as a wounded refugee living with a number of other Belgians in the same situation, there is nothing to absolutely imply that his retirement was due to age. Rather, it was more likely due to the fact that he had been forced from his country by the Germans, causing him to lose his profession. (It’s also likely that he had already stopped being a policeman in order to fight the Germans after their invasion two years before.) Additionally, it’s possible that he “retired” due to the injury that he had in that early book, and many afterwards, which gave him a limp and required him to use a cane.

Next, one must remember that to Hastings, always someone oblivious at best, anyone older than him might seem elderly. Therefore, he might dismiss Poirot, certainly only his mid-forties during the War, at times because of his age. That would be due to Hastings’ perception and attitudes about persons older than himself, and not necessarily because Poirot was, in fact, old.

One might recall that at times others also implied that Poirot was elderly. But might this not have been one of the affectations that he used so skillfully in order to keep people from taking him too seriously, while he recorded every fact that he observed for further use? On several occasions, Poirot privately admitted that his too-strong accent, his mannerisms, and even some of his comical behaviors, were carefully contrived so that he might be ignored while he observed and built his cases. No doubt this was also quite effective when he was a Belgian policeman. (I believe that the American detective, Columbo – whose adventures I have never read or watched – used much the same method.) And maybe, just maybe, some of these factors were also exaggerated by Agatha Christie, the Literary Agent who presented so many – but not all! – of Poirot’s adventures to the world, for her own purposes. After all, it’s said that she didn’t like Poirot very much, so maybe she found ways to subtly diminish him.

It’s been related that Christie recorded the events of Poirot’s last case, Curtain, in the middle of World War II, when she, living in London, feared that she would be killed by German bombs. That book, along with the final Miss Marple book, Sleeping Murder, (published in 1976), was stored in a bomb-proof safe. Only at the end of her life, in the 1970’s, did Christie allow these books to be revealed.

If Curtain was in fact recorded in the early wartime 1940’s, then Poirot would have already been dead by then. But since he lived for a bit longer, I suspect that whatever book Christie, as Literary Agent, actually stored in that safe was some other Poirot case – possibly something so shocking that the world was not yet prepared for it – and that the book was not Curtain.

Some would insist that since ten Poirot adventures were published from the 1950’s through the 1970’s, this is an indication that he was still alive and functioning during that entire time. After all, these books contain elements related specifically to those decades which must certainly tie the story to the years in which they were published. I maintain that these cases, all published after Poirot’s death in 1949, were updated by Christie by inclusion of various sentences or references here-and-there in order to make them seem as if they were occurring contemporary to their publication. Actually, these ten tales all took place during the short period between the end of World War II in 1945, and Poirot’s death four years later.

(Many also take the position that Nero Wolfe magically did not age throughout the decades when his adventures were being published. Coincidentally, the final Wolfe book presented by Literary Agent Rex Stout, A Family Affair, was published in May 1975, within months of the September 1975 appearance of Curtain. Similar to Poirot’s situation, wherein later adventures were updated to appear contemporary with publication, I believe that the final two Wolfe books, 1973’s Please Pass the Guilt and A Family Affair, were altered to seem as if they were occurring in the 1970’s, when they actually took place in the late 1960’s, and that Wolfe died in 1971 at the ripe old age of 79 – quite an accomplishment for someone who had such an adventurous and dangerous youth, and who maintained such a sedentary and well-fed middle-age onward.)

Based on the idea of cases updated to seem up-to-the-minute, the following Poirot adventures actually occurred in the late 1940’s, rather than near the time of their publication dates . . . .

• Mrs McGinty's Dead (a.k.a. Blood Will Tell) (Published in 1952)

• After the Funeral (a.k.a. Funerals are Fatal) (1953)

• Hickory Dickory Dock (a.k.a. Hickory Dickory Death) (1955)

• Dead Man's Folly (1956)

• Cat Among the Pigeons (1959)

• The Clocks (1963)

• Third Girl (1966)

• Hallowe'en Party (1969)

• Elephants Can Remember (1972)

• Curtain (1975)

. . . and therefore it’s quite foolish to think that Poirot was well over one-hundred years old at his death.

From the facts in the books, I postulate that Poirot was born in 1870. This is supported by the story “The Penultimate Problem”, as related by someone with the unique sobriquet, “SolarPenguin”. Dated April 27th, 1891, it’s a short narrative from the diaries of Dr. John H. Watson, recounting a conversation that he and Sherlock Holmes were having in Belgium while both were unknowingly headed toward a rendezvous with Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls on May 4th. They are interrupted by “a young Belgian, a small man with a large moustache” who tells them that:

“I have recently joined the Belgian police force because I hope to become a detective. What interests me about such work is not your dull, scientific tasks of analysing shirt-cuffs or tobacco ash. Mais non, c'est la psychologie. Using the little grey cells of my mind to enter the mind of someone else – the criminal.”

This little adventure can be found at: https://www.fanfiction.net/s/226768/1/The-Penultimate-Problem

Interlude: Poirot and Sherlock Holmes

This story, "The Penultimate Problem", is important, because it helps to link Poirot to that greater world of Master Sleuths, of whom the most prominent citizen is my greatest hero, Sherlock Holmes. (Some people are fanatics for sports teams. Not me. I’m a Missionary for The Church of Sherlock Holmes.) Holmes also encounters Poirot in Julian Symons’ tale, “Did Sherlock Holmes Meet Hercule - ?” But I believe that they had other contacts as well.

Since discovering Sherlock Holmes in 1975, I’ve played The Game with deadly seriousness. This mean that Holmes and Watson are considered to be have been real historical figures, and not characters in stories. Related to this, I do the same with other individuals, such as Nero Wolfe, Ellery Queen, Solar Pons, and Hercule Poirot. Since the mid-1990’s, I’ve maintained an overall Chronology of the lives of Holmes and Watson, as based upon the stories in the original Holmes Canon, as well as all of those other thousands of traditional narratives that I’ve collected in the form of novels and short stories, radio and television episodes, scripts and movies, fan fictions and unpublished manuscripts. And along the way, I also keep chronologies for Wolfe, Queen, Pons, and Poirot too.

I believe that when Poirot came to England as a refugee in 1916, it was with Holmes’s advice and blessing that he chose to stay and set himself up as a consulting detective at 14 Farraway Street, sharing rooms with Hastings. Additionally, Poirot worked upon occasion with Solar Pons, who had a family relationship with Holmes, and who maintained his own consulting practice at 7B Praed Street, near Paddington Station. In fact, Poirot, thinly disguised as “M. Hercule Poiret” of the French Sûreté, is of assistance in the summer of 1938 in the Pons narrative “The Adventure of the Orient Express”.

In the fall of 2013, I made the first (of three so far) Holmes Pilgrimages to England. I’ve worn a deerstalker as my only hat from the age of nineteen in 1984 to the present, and it was certainly with me on each of those trips as I visited countless Holmes-related sites. I had planned that first trip for literally decades, using more than two-dozen Holmes travel books in my collection, and if a site wasn’t related to Holmes, I pretty much ignored it. (As I’ve related elsewhere, I didn’t go on the London Eye, because it has nothing to do with Holmes, but I did visit The Tower of London – not for its historic or tourist aspects, but because it has figured so importantly in numerous Holmes pastiches.)

I did allow a few non-Holmes sites to creep in. I repeatedly visited the site of Pons’s home at 7B Praed Street, and I even made a pass by No. 30 Wellington Square, James Bond’s flat in Chelsea. And I tried to find Poirot’s lodgings as well.

Before I left on that first trip, I did some Poirot research, and conferred with a number of Poirot experts, with mixed success. One only has to check the maps, then and now, to see that there is no Farraway Street, where Poirot and Hastings lived after the War and into the early 1920’s, and there is no Whitehaven Mansion in Mayfair. Through my own research, I decided that this is the actual No. 14 Farraway Street, about halfway between 7B Praed Street and 221 Baker Street:

And this is the likely location of Whitehaven Mansions in Mayfair:

Of course, while I was there, I couldn’t miss visiting the art deco masterpiece that was used as the exterior for Poirot’s upscale residence, Florin Court in Charterhouse Square, a part of London quite removed from Mayfair, and very unlikely indeed to have a building that would attract Poirot’s specific tastes:

Here is me and my deerstalker at what is recognized by millions as Poirot's residence:

And now, some more About Poirot in the Media

As mentioned, Suchet filmed a majority of the Poirot stories – but not all of them. For instance, Poirot was in a 1930 play, Black Coffee, which was novelized in 1998 by Charles Osborne, but never filmed by Suchet. Other stories, some mentioned previously, that were not adapted for one reason or another include:

• “The Lemesurier Inheritance” from The Labours of Hercules. The television episode only mentioned the name “Lemesurier” in passing;

• “The Market Basing Mystery”, later adapted to become “Murder in the Mews”.

• “The Submarine Plans”, which became “The Incredible Theft”;

• “Christmas Adventure”, later revised as “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”;

• “The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest”, later revised as “The Mystery of the Spanish Chest”;

• “The Second Gong”, which became “Dead Man's Mirror”;

• “The Capture of Cerberus”, a completely alternate version of the same story.

However, even without these stories being filmed, and with some of the others being changed significantly, Suchet’s achievement is unmatched, and he will go down in history as the defining portrayal of Hercule Poirot.

There have been many others who have played the part of Poirot. On radio, he premiered on February 22nd, 1945 on the U.S.’s Mutual Network in “The Careless Victim” with these words:

“Agatha Christie’s Poirot! From the thrill-packed pages of Agatha Christie’s unforgettable stories of corpses, clues, and crime, Mutual now brings you, complete with bowler hat and brave mustache, your favorite detective . . . Hercule Poirot!

The episode, which can be heard here . . .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8TMW87LJUk

. . . then opened with a statement from Agatha Christie herself. It was originally planned to have her, in England, join the beginning of the live American broadcast, but due to transmission problems – “atmospheric conditions” – a pre-recorded version (wisely obtained earlier in the day just in case) was used, allowing the Literary Agent to speak. It’s a treat to hear her state that:

“I feel that this is an occasion that would have appealed to Hercule Poirot. He would have done justice to the inauguration of this radio program, and he might even have made it feel something of an international event. However, since he is heavily engaged on an investigation, about which you will hear in due course, I must, as one of his oldest friends, deputize for him. The great man has his little foibles, but really I have the greatest affection for him, and it is a source of continuing satisfaction to me that there has been such a generous response to his appearance on my books, and I hope that his new career on the radio will make many new friends for him among a wider public.”

One has to wonder what Christie really thought, as these broadcasts were billed as Poirot’s adventures in America, with the Belgian now living in New York! (In spite of that unusual feature, they hold up well, and add to the overall Poirot Tapestry.)

For the BBC, John Moffatt played Poirot extremely well in at least twenty-five adaptations, and for many fans, he became the voice of Poirot.

On stage and in film, Poirot has been played by several actors. There was the famed Charles Laughton in 1928’s play Alibi, based upon The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

This was later filmed in 1931, with Austin Trevor becoming the first screen Poirot – although without a mustache!

(Trevor followed up with a film of Black Coffee in 1931.)

There would be a long gap before Poirot would next be seen on screen, in 1966’s The Alphabet Murders, based upon the book The ABC Murders (1936). Interestingly, this film also had Austin Trevor, but now playing a character named Judson. Presented as a comedy and painful to watch, it starred Tony Randall with a bald head and mustache as Poirot, playing him as an exaggerated buffoon:

It also featured an amazingly poorly cast Robert Morley, (who had played Mycroft Holmes much more effectively the year before in A Study in Terror) as Hastings. One should watch this film for completeness . . . and then walk away.

The Poirot World was rocked with amazement and pleasure in 1974’s incredible Murder on the Orient Express, the first of many times that this book has been filmed. Albert Finney literally became Poirot, and to many this was both the best portrayal and best adaptation.

Sadly, it appeared several years before I discovered Poirot in 1978, so I came to it late, after Poirot was already firmly set in my mind in a non-Finney way. While I still greatly admire the film, I found Finney to be difficult to understand at times, and when I later saw David Suchet’s 2010 version of Murder on the Orient Express, I was satisfied that his was the definitive portrayal.

Some find Suchet’s version too dark, but I felt that it’s his best turn as Poirot. The 1974 film – and even the book somewhat – don’t go far enough in portraying the discomfort of being on a train that is trapped in a snowy wasteland while a murder has been committed. And Suchet makes Poirot’s outrage at the terrible sin and violation and disorder of murder – and also the danger in which he found himself after revealing the solution – crystal clear. When Poirot makes his decision at the end of the story, his pain is palpable. (Compare this to the end of the 1974 version, which is almost festive – a twinkle of the eye from Poirot as he presents his alternative solutions, and then announces that the murder will go unpunished. Cue the relieved smiles and hugs and celebratory music.)

As mentioned, there have been five film adaptations of Murder on the Orient Express. One really can’t ignore the unspeakable modern-day made-for-television version from 2001 starring Alfred Molina.

The original story is buried in there somewhere, but the filmmakers have done the same abominable thing that happened with the BBC Sherlock, modernizing what should not be modernized. At least Molina’s Poirot isn't a murderous sociopathic creep. Watch it if you can:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9rEAkwz5EZc

There was also a Japanese version of Murder on the Orient Express from 2015, with the events of the mystery moved to 1926 Japan.

I haven’t seen it, and can’t understand it, but here’s the trailer. It’s . . . curious:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JW-bgw-Wb04

And then there was the video game version from 2006, with Poirot voiced by David Suchet himself – interestingly, before he was in the film 2010 version:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=alDvqfcpMVs

Finally, there is the most recent 2017 version, which prompted me to write this essay, starring Sir Kenneth Branagh as Poirot.

Months before the November 2017 release, photos were released of the various cast members, and the Poirot World was set aflame with photos of Branagh’s version of Poirot’s mustache.

Some called it a “hemp gag”, while others – well, me for sure anyway, and probably others too – described it as “road kill”. I was pretty vocal in my concern about it, and I was taken to task by several for not giving the film a chance.

One of my great pet peeves, right up there with line-cutters and One-Percenters, is when a screen adapter takes a classic work – especially one of my own favorites – something that has only grown in popularity for generations, and that is popular for so long for a reason, and is actually worthy of being filmed, and then rewrites it because he/she believes that his own vision is actually better than that of the original work. It’s supremely arrogant, and in the case of this film, and particularly the use of that Monster Mustache, I was convinced that the film makers were disrespecting Poirot to serve their own misguided visions.

I was wrong. So very wrong. I’m happy to admit it. There’s no denying that the mustache is initially and distractingly huge. And odd. And it's played by an actor named Felix Silla. But the distraction quickly goes away. The story itself has a few changes and additions, but they don’t veer too far from the basic narrative – they are all something that could have happened in the book, but just didn’t quite get recorded. The vistas in the opening of the film – even if they are computer generated and proof that if anything can now be imagined, it can be shown on film – are not to be missed. I felt like I was in Istanbul, boarding The Orient Express for that fateful journey, and then a part of the action as it made it's way to that inevitable spot where justice would be enacted.

Both Branagh’s directing and portrayal of Poirot are exceptional. I expect that he is far too busy and has too many other projects and interests to play Poirot again . . . but I hope that he does. David Suchet will always be the best Poirot to me, and he filmed almost every one of the original stories, but I would be more than happy to see Branagh also take on as many of Poirot’s cases as he can.

What's next?

The future of Poirot seems secure. Interest in the amazing Belgian detective and his “little grey cells” only increases with each passing year, and with the promise of new stories in the works, additional aspects of Poirot’s life will certainly be revealed.

Additionally, the end of the 2017 version Murder on the Orient Express features Poirot being called back to Egypt, with news of a murder “right on the bloody Nile.”

A reference to Death on the Nile? Perhaps. And if they do film that one, my deerstalker and I will be there to watch it, just like we were on November 11th, 2017 to see Murder on the Orient Express. And just like that thirteen-year-old boy in 1978 that was me who first met Hercule Poirot when there was a Death on the Nile, this fifty-something-year-old man will be tagging along on the Karnak as it sets sail through 1930’s Egypt. It might initially seem like a peaceful trip, but as anyone should know, if Hercule Poirot is around, there’s going to be a murder.

©David Marcum 2017 – All Rights Reserved

*************************

David Marcum plays The Game with deadly seriousness. He first discovered Sherlock Holmes in 1975 at the age of ten, and since that time, he has collected, read, and chronologicized literally thousands of traditional Holmes pastiches in the form of novels, short stories, radio and television episodes, movies and scripts, comics, fan-fiction, and unpublished manuscripts. He is the author of over sixty Sherlockian pastiches, some published in anthologies and magazines such as The Strand, and others collected in his own books, The Papers of Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock Holmes and A Quantity of Debt, and Sherlock Holmes – Tangled Skeins. He has edited over fifty books, including several dozen traditional Sherlockian anthologies, such as the ongoing series The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories, which he created in 2015. This collection is now up to 21 volumes, with several more in preparation. He was responsible for bringing back August Derleth’s Solar Pons for a new generation, first with his collection of authorized Pons stories, The Papers of Solar Pons, and then by editing the reissued authorized versions of the original Pons books. He is now doing the same for the adventures of Dr. Thorndyke. He has contributed numerous essays to various publications, and is a member of a number of Sherlockian groups and Scions. He is a licensed Civil Engineer, living in Tennessee with his wife and son. His irregular Sherlockian blog, A Seventeen Step Program, addresses various topics related to his favorite book friends (as his son used to call them when he was small), and can be found at http://17stepprogram.blogspot.com/ Since the age of nineteen, he has worn a deerstalker as his regular-and-only hat. In 2013, he and his deerstalker were finally able make his first trip-of-a-lifetime Holmes Pilgrimage to England, with return Pilgrimages in 2015 and 2016, where you may have spotted him. If you ever run into him and his deerstalker out and about, feel free to say hello!

His Amazon Author Page can be found at:

https://www.amazon.com/kindle-dbs/entity/author/B00K1IKA92?_encoding=UTF8&node=283155&offset=0&pageSize=12&searchAlias=stripbooks&sort=author-sidecar-rank&page=1&langFilter=default#formatSelectorHeader

and at MX Publishing:

https://mxpublishing.com/search?type=product&q=marcum&fbclid=IwAR12tH4SUvE9nmEnnuqeI5GC7Tv69-NagPgmAZlxcz0vr2Ihza5_6jP-fXM